Introduction – using babelmixr2 with PopED

babelmixr2 now introduces a new method that takes

rxode2/nlmixr2 models converts them to a

PopED database to help with optimal design.

As in the PopED vignette comparing ODE solvers (and their speeds), this section will:

take the model described and adapt it in two different

rxode2model functions, the solved and ode cases (this is done by thenlmixr()call which creates aPopEDdatabase)compare these examples to the pharmacometric solvers in the PopED vignette (

mrgsolve, originalrxode2andPKPDsim)

babelmixr2 ODE solution

The first step of a design using babelmixr2 is to tell babelmixr2

about the design being optimized. This is a bit different than what is

done in PopED directly. Below I am using the

et() function to create the event table like a typical

rxode2 simulation, but it is used to specify the study

design:

library(babelmixr2)

library(PopED)

e <- et(amt=1, ii=24, until=250) %>%

et(time=c(1,2,8,240,245)) %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

dplyr::mutate(low=c(NA_real_, 0, 0, 0, 240, 240),

high=c(NA_real_, 10, 10, 10, 248, 248))

print(e)

#> time amt ii addl evid low high

#> 1 0 1 24 10 1 NA NA

#> 2 1 NA NA NA 0 0 10

#> 3 2 NA NA NA 0 0 10

#> 4 8 NA NA NA 0 0 10

#> 5 240 NA NA NA 0 240 248

#> 6 245 NA NA NA 0 240 248PopED/babelmixr2 event table description

Here note that time is the design times for the

PopED designs, they can include dosing; only observations

are considered the time-points. They become the xt

parameter in the PopED database (excluding the doses).

We also build on the structure of the rxode2 event table

with simulations. In simulations the sampling windows cause random times

to be generated inside the sampling windows. For this reason, the last

line of code fixes the times to where we want to have the multiple

endpoint design.

Therefore, in this dataset the low becomes

minxt and high becomes maxxt.

We chose these because they build on what is already know from

nlmixr2 and used in and do not require any extra

coding.

Other things you may have to include in your PopED model

data frame are:

dvidwhich gives the integer of the model endpoint measured (likerxode2but has to be an integer). This becomesmodel_switchin thePopEDdataset.G_xtwhich is thePopEDgrouping variable; This will be put into thePopEDdatabase asG_xtidbecomes an ID for a design (which you can use as a covariate to pool different designs or different regimens for optimal design).

Getting PopED functions from

nlmixr2/rxode2 ui function

Once the design is setup, we need to specify a model. It is easy to

specify the model using the nlmixr2/rxode2

function/ui below:

# model

f <- function() {

ini({

tKA <- 0.25

tCL <- 3.75

tV <- 72.8

Favail <- fix(0.9)

eta.ka ~ 0.09

eta.cl ~ 0.25 ^ 2

eta.v ~ 0.09

prop.sd <- sqrt(0.04)

add.sd <- sqrt(0.0025)

})

model({

ka <- tKA * exp(eta.ka)

v <- tV * exp(eta.v)

cl <- tCL * exp(eta.cl)

d/dt(depot) <- -ka * depot

d/dt(central) <- ka * depot - cl / v * central

cp <- central / v

f(depot) <- DOSE * Favail

cp ~ add(add.sd) + prop(prop.sd)

})

}

f <- f() # compile/check nlmixr2/rxode2 model

# Create a PopED database for `nlmixr2`:

poped_db_ode_babelmixr2 <- nlmixr(f, e, "poped",

popedControl(a=list(c(DOSE=20),

c(DOSE=40)),

maxa=c(DOSE=200),

mina=c(DOSE=0)))

#> ℹ groupsize should be specified; but for now assuming 20

#> ℹ assuming group size m=2

#> using C compiler: ‘gcc (Ubuntu 11.4.0-1ubuntu1~22.04) 11.4.0’

#>

#> using C compiler: ‘gcc (Ubuntu 11.4.0-1ubuntu1~22.04) 11.4.0’Note when creating a PopED database with a model and a

design event table, many of the PopED database components

are generated for you.

These are not things that are hidden, but things you can access

directly from the model or even from the compiled ui. Much

of the other options for optimal design can be specified with the

popedControl() function.

This can help you understand what babelmixr2 is doing,

we will show what is being added:

PopED’s ff_fun from babelmixr2

This is the function that is run to generate the predictions:

# The ff_fun can be retrieved from the ui with f$popedFfFun

f$popedFfFun

#> function (model_switch, xt, p, poped.db)

#> {

#> .xt <- drop(xt)

#> .id <- p[1]

#> .u <- .xt

#> .lu <- length(.u)

#> .totn <- length(.xt)

#> if (.lu <= 5L) {

#> poped.db <- .popedRxRunSetup(poped.db)

#> .p <- babelmixr2::popedMultipleEndpointParam(p, .u, model_switch,

#> 5L, poped.db$babelmixr2$optTime)

#> .ret <- try(.popedSolveIdME(.p, .u, .xt, model_switch,

#> 1L, .id - 1, .totn), silent = TRUE)

#> }

#> else if (.lu > 5L) {

#> .p <- p[-1]

#> poped.db <- .popedRxRunFullSetupMe(poped.db, .xt, model_switch)

#> .ret <- try(.popedSolveIdME2(.p, .u, .xt, model_switch,

#> 1L, .id - 1, .totn), silent = TRUE)

#> }

#> return(list(f = matrix(.ret$rx_pred_, ncol = 1), poped.db = poped.db))

#> }

#> <environment: 0x560677b0bd08>Some things to note in this function:

The model changes based on the number of time-points requested. In this case it is

5since there were5design points in the design above.-

There are some

babelmixr2specific functions here:babelmixr2::popedMultipleEndpointParam, which indexes the time input and model_input to make sure the input matches as requested (in many PopED functions they usematch.timeand this is a bit similar)..popedRxRunSetup/.popedRxRunFullSetupMewhich runs the rxode2 setup including loading the data and model into memory (and is a bit different depending on the number of time points you are using).popedSolveIdME/.popedSolveIdME2which solves the rxode2 model and uses the indexes to give the solve used in the model.

rxode2 models generated from babelmixr2

By describing this, you can also see that there are 2

rxode2 models generated for the PopED

database. You can see these inside of the PopED database as well.

The first model uses model times to solve for arbitrary times based on design:

summary(poped_db_ode_babelmixr2$babelmixr2$modelMT)

#> rxode2 3.0.4 model named rx_b91e48be149288115c2b659a8c70ad84 model (✔ ready).

#> DLL: /tmp/RtmpeV9LVK/rxode2/rx_b91e48be149288115c2b659a8c70ad84__.rxd/rx_b91e48be149288115c2b659a8c70ad84_.so

#> NULL

#>

#> Calculated Variables:

#> [1] "rx_pred_" "rx_r_"

#> ── rxode2 Model Syntax ──

#> rxode2({

#> param(rx__tKA, rx__tCL, rx__tV, rx__eta.ka, rx__eta.v, rx__eta.cl,

#> DOSE, rxXt_1, rxXt_2, rxXt_3, rxXt_4, rxXt_5)

#> ka ~ rx__tKA * exp(rx__eta.ka)

#> v ~ rx__tV * exp(rx__eta.v)

#> cl ~ rx__tCL * exp(rx__eta.cl)

#> d/dt(depot) = -ka * depot

#> d/dt(central) = ka * depot - cl/v * central

#> cp ~ central/v

#> f(depot) = DOSE * 0.9

#> rx_yj_ ~ 2

#> rx_lambda_ ~ 1

#> rx_low_ ~ 0

#> rx_hi_ ~ 1

#> rx_pred_f_ ~ cp

#> rx_pred_ = rx_pred_f_

#> rx_r_ = (0.05)^2 + (rx_pred_f_)^2 * (0.2)^2

#> mtime(rxXt_1_v) ~ rxXt_1

#> mtime(rxXt_2_v) ~ rxXt_2

#> mtime(rxXt_3_v) ~ rxXt_3

#> mtime(rxXt_4_v) ~ rxXt_4

#> mtime(rxXt_5_v) ~ rxXt_5

#> })You can also see the model used for solving scenarios with a number of time points greater than the design specification:

summary(poped_db_ode_babelmixr2$babelmixr2$modelF)

#> rxode2 3.0.4 model named rx_d3ebcd21cc044a210aaaea444e2e3db9 model (✔ ready).

#> DLL: /tmp/RtmpeV9LVK/rxode2/rx_d3ebcd21cc044a210aaaea444e2e3db9__.rxd/rx_d3ebcd21cc044a210aaaea444e2e3db9_.so

#> NULL

#>

#> Calculated Variables:

#> [1] "rx_pred_" "rx_r_"

#> ── rxode2 Model Syntax ──

#> rxode2({

#> param(rx__tKA, rx__tCL, rx__tV, rx__eta.ka, rx__eta.v, rx__eta.cl,

#> DOSE)

#> ka ~ rx__tKA * exp(rx__eta.ka)

#> v ~ rx__tV * exp(rx__eta.v)

#> cl ~ rx__tCL * exp(rx__eta.cl)

#> d/dt(depot) = -ka * depot

#> d/dt(central) = ka * depot - cl/v * central

#> cp ~ central/v

#> f(depot) = DOSE * 0.9

#> rx_yj_ ~ 2

#> rx_lambda_ ~ 1

#> rx_low_ ~ 0

#> rx_hi_ ~ 1

#> rx_pred_f_ ~ cp

#> rx_pred_ = rx_pred_f_

#> rx_r_ = (0.05)^2 + (rx_pred_f_)^2 * (0.2)^2

#> })You can also see that the models are identical with the exception of

requesting modeled times. You can see the base/core rxode2

model form the UI here:

f$popedRxmodelBase

#> [[1]]

#> ka ~ rx__tKA * exp(rx__eta.ka)

#>

#> [[2]]

#> v ~ rx__tV * exp(rx__eta.v)

#>

#> [[3]]

#> cl ~ rx__tCL * exp(rx__eta.cl)

#>

#> [[4]]

#> d/dt(depot) <- -ka * depot

#>

#> [[5]]

#> d/dt(central) <- ka * depot - cl/v * central

#>

#> [[6]]

#> cp ~ central/v

#>

#> [[7]]

#> f(depot) <- DOSE * rx__Favail

#>

#> [[8]]

#> rx_yj_ ~ 2

#>

#> [[9]]

#> rx_lambda_ ~ 1

#>

#> [[10]]

#> rx_low_ ~ 0

#>

#> [[11]]

#> rx_hi_ ~ 1

#>

#> [[12]]

#> rx_pred_f_ ~ cp

#>

#> [[13]]

#> rx_pred_ <- rx_pred_f_

#>

#> [[14]]

#> rx_r_ <- (0.05)^2 + (rx_pred_f_)^2 * (0.2)^2PopED’s fg_fun

babelmixr2 also generates PopEDs

fg_fun, which translates covariates and parameters into the

parameters required in the ff_fun and used in solving the

rxode2 model.

# You can see the PopED fg_fun from the model UI with

# f$popedFgFun:

f$popedFgFun

#> function (rxPopedX, rxPopedA, bpop, b, rxPopedBocc)

#> {

#> rxPopedDn <- dimnames(rxPopedA)

#> rxPopedA <- as.vector(rxPopedA)

#> if (length(rxPopedDn[[1]]) == length(rxPopedA)) {

#> names(rxPopedA) <- rxPopedDn[[1]]

#> }

#> else if (length(rxPopedDn[[2]]) == length(rxPopedA)) {

#> names(rxPopedA) <- rxPopedDn[[2]]

#> }

#> ID <- setNames(rxPopedA[1], NULL)

#> DOSE <- setNames(rxPopedA["DOSE"], NULL)

#> tKA <- bpop[1]

#> tCL <- bpop[2]

#> tV <- bpop[3]

#> Favail <- bpop[4]

#> eta.ka <- b[1]

#> eta.v <- b[3]

#> eta.cl <- b[2]

#> rx__tKA <- tKA

#> rx__tCL <- tCL

#> rx__tV <- tV

#> rx__Favail <- Favail

#> rx__eta.ka <- eta.ka

#> rx__eta.v <- eta.v

#> rx__eta.cl <- eta.cl

#> c(ID = ID, rx__tKA = setNames(rx__tKA, NULL), rx__tCL = setNames(rx__tCL,

#> NULL), rx__tV = setNames(rx__tV, NULL), rx__Favail = setNames(rx__Favail,

#> NULL), rx__eta.ka = setNames(rx__eta.ka, NULL), rx__eta.v = setNames(rx__eta.v,

#> NULL), rx__eta.cl = setNames(rx__eta.cl, NULL), DOSE = setNames(DOSE,

#> NULL))

#> }

#> <environment: 0x560676232098>PopED’s error function fError_fun

You can see the babelmixr2 generated error function as

well with:

f$popedFErrorFun

#> function (model_switch, xt, parameters, epsi, poped.db)

#> {

#> rxReturnArgs <- do.call(poped.db$model$ff_pointer, list(model_switch,

#> xt, parameters, poped.db))

#> rxF <- rxReturnArgs[[1]]

#> rxPoped.db <- rxReturnArgs[[2]]

#> rxErr1 <- rxF * (1 + epsi[, 1]) + epsi[, 2]

#> return(list(y = rxErr1, poped.db = rxPoped.db))

#> }

#> <environment: 0x56066b9b2810>One really important note to keep in mind is that PopED

works with variances instead of standard deviations (which is a key

difference between nlmixr2 and PopED).

This means that the exported model from babelmixr2

operates on variances instead of standard deviations and care must be

taken in using these values to not misinterpret the two.

The export also tries to flag this to make it easier to remember.

Other parameters generated by PopED

f$popedBpop # PopED bpop

#> tKA tCL tV Favail

#> 0.25 3.75 72.80 0.90

f$popedNotfixedBpop # PopED notfixed_bpop

#> [1] 1 1 1 0

f$popedD # PopED d

#> eta.ka eta.cl eta.v

#> 0.0900 0.0625 0.0900

f$popedNotfixedD # PopED notfixed_d

#> NULL

f$popedCovd # PopED covd

#> NULL

f$popedNotfixedCovd # PopED notfixed_covd

#> NULL

f$popedSigma # PopED sigma (variance is exported, not SD)

#> prop.var add.var

#> 0.0400 0.0025

f$popedNotfixedSigma # PopED notfixed_sigma

#> prop.var add.var

#> 1 1The rest of the parameters are generated in conjunction with the

popedControl().

linear compartment models in babelmixr2

You can also specify the models using the linCmt()

solutions as below:

f2 <- function() {

ini({

tV <- 72.8

tKA <- 0.25

tCL <- 3.75

Favail <- fix(0.9)

eta.ka ~ 0.09

eta.cl ~ 0.25 ^ 2

eta.v ~ 0.09

prop.sd <- sqrt(0.04)

add.sd <- fix(sqrt(5e-6))

})

model({

ka <- tKA * exp(eta.ka)

v <- tV * exp(eta.v)

cl <- tCL * exp(eta.cl)

cp <- linCmt()

f(depot) <- DOSE

cp ~ add(add.sd) + prop(prop.sd)

})

}

poped_db_analytic_babelmixr2 <- nlmixr(f, e,

popedControl(a=list(c(DOSE=20),

c(DOSE=40)),

maxa=c(DOSE=200),

mina=c(DOSE=0)))

#> ℹ infer estimation `poped` from control

#> ℹ groupsize should be specified; but for now assuming 20

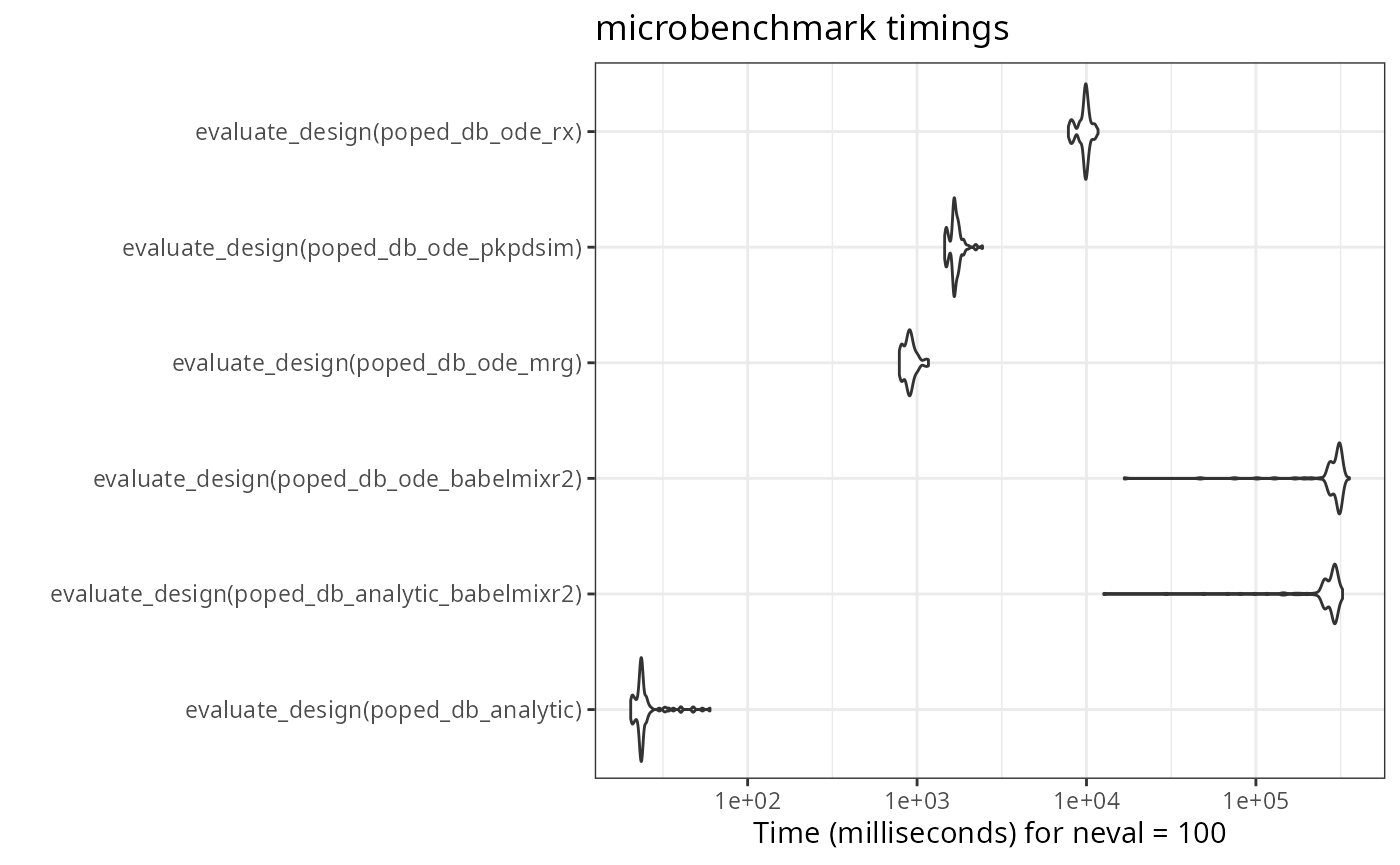

#> ℹ assuming group size m=2Comparing method to the speed of other methods

library(ggplot2)

library(microbenchmark)

compare <- microbenchmark(

evaluate_design(poped_db_analytic),

evaluate_design(poped_db_analytic_babelmixr2),

evaluate_design(poped_db_ode_babelmixr2),

evaluate_design(poped_db_ode_mrg),

evaluate_design(poped_db_ode_pkpdsim),

evaluate_design(poped_db_ode_rx),

times = 100L)

autoplot(compare) + theme_bw()

Note that the babelmixr2 ode solution is the fastest ode

solver in this comparison. Among other things, this is because the model

is loaded into memory and does not need to be setup each time. (As

benchmarks, the mrgsolve, and PKPDsim

implementations on the PopED’s website are included).

Also to me, the speed of all the tools are reasonable. In my opinion,

the benefit of the babelmixr2 interface to

PopED is the simplicity of using nlmixr2 /

rxode2 functional models or fits directly in

PopED without relying on conversions.

The interface is a bit different than the traditional

PopED interface, and requires a design data-set as well as

a popedControl() to setup a PopED database to

run all of the PopED tasks. This is because traditionally

nlmixr2 takes a dataset, “estimation” method and controls

to change estimation method options.

babelmixr2 adopts the same paradigm of model, data,

control to be applied to PopED. This should allow easy

translation between the systems. With easier translation, hopefully

optimal design in clinical trials will be easier to achieve.

Key notes to keep in mind

babelmixr2loads models into memory and needs to keep track of which model is loaded. To help this you need to usebabel.poped.databasein place ofcreate.poped.databasewhen modifying babelmixr2 generatedPopEDdatabases. If this isn’t done, there is a chance that the model loaded will not be the expected loaded model and may either crash R or possibly give incorrect results.babelmixr2translates all error components to variances instead of the standard deviations in thenlmixr2/rxode2modelWhen there are covariances in the

omegaspecification, they will be identified asD[#,#]in thePopEDoutput. To see what these numbers refer to it is helpful to see the name translations with$popedD.Depending on your options,

babelmixr2may literally fix the model components, which means indexes may be different than you expect. The best way to get the correct index is use thebabelmixr2functionbabelBpopIdx()which is useful for usingPopEDbabelmixr2uses model times in creatingPopEDdatabases; therefore models with modeling times in them cannot be used in this translationbabelmixr2does not yet support inter-occasion variability models.

Where to find more examples

The examples from PopED have been converted to work with

babelmixr2 and are available in the package and on GitHub